INTRODUCTION

Kaduthuruthy cross is the tallest free-standing rock cross in India and often cited as the highest open-air cross in Asia, made out from a single block. The Travancore Archaeological Series (Volume 7, 1931) refers to the Kaduthuruthy cross as the best of its kind in Travancore. Typically, open-air granite crosses in Kerala are erected in the western courtyard facing the façade and the main entrance of the church. However, Kaduthuruthy cross is positioned in the eastern courtyard at the rear end, i.e. behind the main altar of the Kaduthuruthy St. Mary's Knanaya Catholic Forane Church (Valiyapally). No doubt the cross was considered an impressive monument at the time of its erection. In the old song of the cross, the author asks "is there any cross in Kerala like this?”. Miraculous stories are often associated with the cross such as, at the time of its foundation, Mother Mary herself appeared as an old woman to help the struggling devotees to erect the tall massive structure; and the Vadakkankur king, who, when denied the chalice of the church for the marriage feast of his daughter, attacked Kaduthuruthy church, but the effort of king's elephants and men to destroy the cross failed miserably (Menachery, 1973).

HOW OLD IS THE KADUTHURUTHY CROSS?

Unlike most of the open-air granite crosses in Kerala whose date of establishment cannot be accurately estimated, Kaduthuruthy cross remains one of the few exceptions. We know the details of its establishment from the Jornada of Gouvea, published in 1606. Gouvea describes the visit of Latin Archbishop Menezs to Kaduthuruthy during the Passion Week of 1599, and the consecration the cross on the Resurrection day (Easter). In the year 1599, Easter Sunday fell on 11th April, and Gouvea clarifies that the cross was erected two years ago, which would then place its establishment in the year 1597. The text is Jornada gives the following description about the cross: “As the procession (of Easter Sunday celebrations) reached the compound of the church, they had made a Cross in its middle, quite big, of stone, very beautiful, since two years, and with its foot very well adorned, which still did not have the night lamp according to the custom they observed among themselves, neither did they decorate it like the others because it was not yet dedicated and blessed, because all these big Crosses are to be blessed by their Prelate before they are decorated and feasts are celebrated in their honour, for the veneration in all is the same, and when they came to this one they asked the Archbishop, who was their Prelate, to bless the Cross, which he did with the Pontifical blessing of the new Cross” (Malekandathil, 2003, p. 194)

Another clue we get is from the old songs of Kaduthuruthy Valiyapally (Pallipattu) and of its famed cross (Kurishinte Pattu), which were orally transmitted, and first published in 1910 by Lukas P. A., in his classic work, ‘Malayalathe Suriyani Christhianikalude Purathanapattukal’ (Malayalam), a collection of the ancient songs of the Syrian Christians of Malabar. Lukas (1910, p.68) estimates the date of the cross as 1596 based on the song of Kaduthuruthy Cross:

Stanza 4, Lines 15-19:

കന്നിതന്നരുളാൽ കുരിശന്നു നിറവേറിതെ

കുംഭമേഴും* മീനമെഴുനൂറ്റിമുപ്പതാംകാലം**

കുംഭമേഴും മൂന്നോടൊന്നായ് നിന്ന വ്യഴാഴ്ച്ചനാൾ

വെച്ച കുരിശിച്ഛനൾകു൦ ആലാഹായരുളാലെ

കേരളത്തിലുണ്ടോ കുരിശിങ്ങനെയൊരിടത്തു൦

He applies ‘Paralperu’, an alphabet-numeric code (Chronogram) known in Kerala traditions to the word “കുംഭം” in the line 16 of 4th stanza, and arrives at the Malayalam Era (M. E.) or Kollam Era 771 [41* + 730** = 771] which corresponds to 1596 A. D. In Paralperu system, since numbers are read from right to left, ‘കുംഭം’ [ക=1 and ഭ=4] gets the numerical value of 41. Similarly, based on the Kaduthuruthy Pallippattu, the date of the construction of the church has been estimated as 631 M.E., which corresponds to 1455-56 A.D. Lukas (1910, p. 64) again uses Paralpperu to the word “കാലത്തു” in the 5th line of the Pallippattu (Song of Kaduthuruthy Valiyapally): “കാലത്തു പള്ളി കടുത്തുരുത്തിൽ”. Thus, ക=1, ല=3, and ത=6, when read from right to left is being rendered as 631 M. E. In addition, on the northern wall of the same church is an old inscription in Vatteluttu (old Malayalam script) which says that in the 1590th year of the birth of Lord Jesus, on the occasion of the enlarging of the Kaduthuruthy church building, Mar Abraham and four priests laid a foundation stone on the altar. Putting all these dates together and assuming they are valid, then it is possible that at Kaduthuruthy, a church was built in the year 1456 and after nearly a century and half had elapsed, the church was found too small to accommodate the increasing congregation, and consequently enlarged at the time of Mar Abraham in 1590. Bishop Mar Abraham was the last Chaldean (East Syrian) bishop to rule the St. Thomas Christians, and was interred in Angamaly Kizhekkepally (east church) after his demise in the year 1597. It is therefore feasible that an open-air granite was erected after the old Kaduthuruthy church was renovated in 1590, probably somewhere between 1596 and 1597 (1596 according to Parish Directory, 2017), and since Mar Abraham died at the same period, the cross could not be consecrated, and the community had to wait for two more years, until they had a visiting bishop to perform the auspicious ceremony in 1599.

An interesting eyewitness testimony from 1611, by Fr. Christophorus Joam, a Jesuit priest stationed at Kaduthuruthy finds the cross: beautiful and made of marble of fine workmanship; constructed at the cost of a hundred golden pieces; so elegantly adorned, that made the pagans to call it ‘a sketch of the heavenly glory’; and because of the miraculous powers attributed to it, even non-Christians made vows with Christians; and that it was lit at night by 160 lamps (cited in Reitz, 2001). It should be noted that the lamps were absent at the time of its consecration in 1599 according to Gouvea, so they were added soon after the blessing of the structure by Archbishop Menezes. Traditional interpretation is that the builders who designed the Kaduthuruthy and Chungam church crosses belonged to the Madura School of sculpture (Cherucheril, 1982)

HOW TALL IS THE KADUTHURUTHY CROSS?

How tall is the cross? The height of the cross together with its pedestal has been variously estimated between 36 to 50 feet. One of the earliest references to the size of the cross was given by Lukas P. A. in 1910 as a footnote to the song of Kaduthuruthy Cross in (Purathanapattukal, p.69), where the height reported is 16.5 kol (cross-12 kol and pedestal- 4.5 kol). A similar measurement is recorded in the Travancore Archaeological Series (A. S. Ramanatha Ayyar edn., 1931, Volume VII, Part II, p. 151), where the author gives the height as 16 kol and equates it to 44 feet. The Kol is a basic unit of length used in Vasthu Shasthra (a traditional Indian system of architecture) and depending on the region it can vary from 63 to 84 cm. Now, if we take the more conventionally accepted unit, i.e., 1 kol =2.36 feet (72 cm), the height must be around 38 feet only. The other estimates include: 39 feet (Menachery, 1973); 40 feet (Cherucheril, 1982); 12 metres (Reitz, 2001), 15 metres or ~49 feet (James, 1979) and 50 feet, i.e. cross-40 feet and pedestal-10 feet (Kurisummoottil, 2008; Parish Directory, 2017). The most recent and probably the most accurate measurement is provided by Jose (2017), and according to his thesis, the cross (upright pole) measures a height of 8.1 metres (26.5 feet), the pedestal 2.8 metres (9.2 feet)-together the size of the full structure is 10.9 metres (35.8 feet), and the length of the horizontal cross arm comes 4 metres. The length of the church is 127 feet and the cross is placed exactly at the same distance from the church claims an article written in the Parish Directory ( 2017).

THE STRUCTURE OF KADUTHURUTHY CROSS

The impressive structure consists of a tall monolithic cross and a large pedestal supporting it. Belgian Jesuit missionary, Fr. Henry Hosten, who visited Kaduthuruthy on February 8, 1924 has given us one of the earliest detailed account of this open-air granite cross. However, the most extensive study conducted on the topic to date, was undertaken by Fr. George Kurisummoottil (2008), and he has literally covered every inch of the structure. Mathew Cherucheril (1982), who wrote an authoritative history of the Kaduthuruthy Valiyapally, has devoted a full chapter to the cross. You can also consult the studies by E. J. James (1979), Punnose and Chacko (1991), Cyriac Jose (2017) etc., for additional information

THE CROSS

The top three arms of the free standing cross are equal in length and their extremities are not flat, instead they are tapering with protruded buds. Kurisummoottil (2008) speculates that these buds symbolise the “tree of life “and gives the cross a tender and graceful appearance, whereas Hosten (1924) identifies them more specifically as lotus buds. The cross is plain and as such is devoid of any designs except for an octagonal shaped geometric pattern at the intersecting central point where the three hands join (more clearly visible on the eastern side).

The base or the pedestal of the Kaduthuruthy cross is intricately carved and is the most noticeable part of the structure. It consists of three mouldings: the larger bottom layer is of square shape, followed by an octagonal middle and a round top section with a lotus design at the summit from which the monolithic cross arises. In religious symbolism, circle stands for divinity and eternity; the eight sides of the octagon and four sides of square represent the quarters of the world (Kurisummoottil, 2008). The most important section of the pedestal lies on the western side, at a cardinal axis facing the main sanctuary of the church, where beautiful carving of pigeons, winged angelic faces, a crucifixion scene, a panel of the exaltation of the Holy Cross, and a statue of Virgin Mary holding infant Jesus are arranged in an orderly fashion from top to bottom.

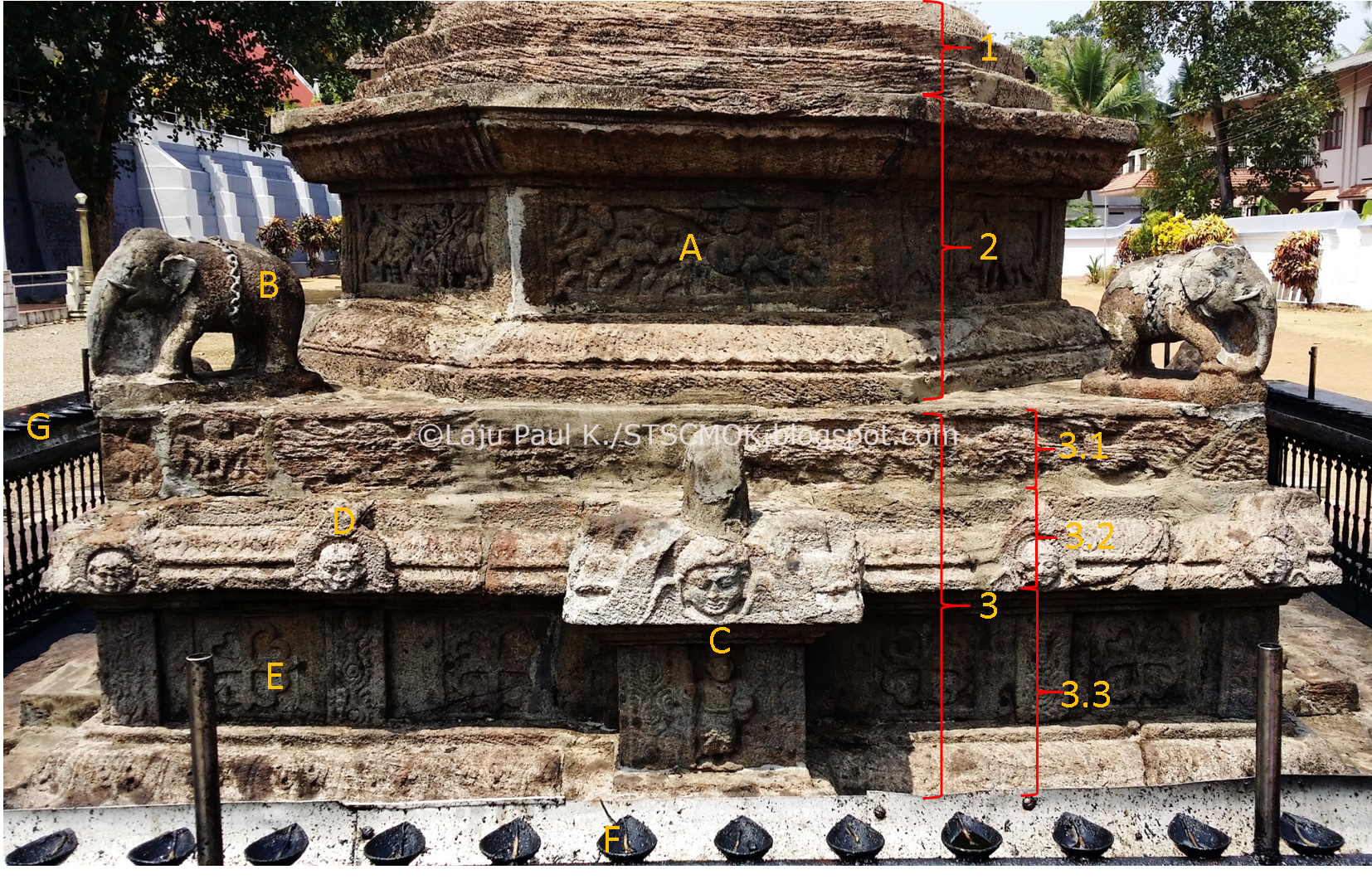

The Structure of the Pedestal of the Cross

1-Round Top Layer; 2-Octagonal Middle Layer; 3-Square Bottom Layer, 3.1-Top Register, 3.2-Middle Register, 3.3-Bottom Register; A-Octagonal Panel; B-Corner Elephant; C-Central Niche; D-Horseshoe Gable Ornamentation; E-Continuous Trefoil Cross; F-Oil Lamp; G-Iron Railing

TOP ROUND SECTION

The layer consists of seven rings of different size and has a lotus pedestal at the top which holds the cross. There are beautiful carving of 4 pigeons in prostrate position, and 6 winged faces (Angels), arranged in the form of a circle. Further down is the most characteristic feature of the moulding, a finely carved crucifixion panel with Christ on the cross flanked by Virgin Mary on the left and St. John the Apostle (Hosten, 1924 and Kurisummoottil, 2008) or Mary Magdalene on the right (Menachery, 1973 and James, 1979). However, if you observe this panel carefully, you will notice that Virgin Mary is holding a child under the cross of Christ, and this has to be an iconographic error by the sculptor says Kurisummoottil (2008).

MIDDLE OCTAGONAL SECTION

The middle octagonal section of the pedestal has eight finely decorated panels depicting biblical events, religious motifs, battle scenes, hunting scenes etc. Each panel is separated from the adjacent one by a vertical band of tendrils and curls. The specific details in these panels have been variously interpreted by different authors, however, a consensus seems to exist regarding the major themes involved. As mentioned earlier, the most important panel among the eight is the one in the western axis which depicts the exaltation and the adoration of the cross. We will go through each of these panels starting from the exaltation relief, and following anti-clockwise order to the rest of the panels in the South-West, South, South-East, East, North-East, North and North-West directions.

Panel-1 (West)-Exaltation of the Cross

The panel depicts the exaltation and adoration of the cross by two paired figures in a kneeling position, where each pair has a male and female member. Now, whom do they represent? Opinions vary among researchers such as the two figures on either side of the cross may be Queen Helena and her son Emperor Constantine (Kurisummoottil, 2008); angels, two on either side (Hosten, 1924); or devotees, two on each side (Jose, 2017).

This panel represents two separate scenes and it is one of the most diversely interpreted. According to Kurisummoottil (2008), the left section is a resurrection icon and could be either Christ with Adam after His descent into the hell or St. Thomas meeting the risen Christ; whereas, the right section is the archangel St. Michael mounted over devil at his feet and facing a monster with wide open mouth and big rounded eye. For Hosten (1924), the scenes are St. Thomas touching Christ's side, and St. Michael with balance and spear standing near an evil monster. There are others who bring Thomas of Cana into the picture, the figure from whom the Knanite community claim their ancestry. Thus, the panel depicts the Catholicos of Baghdad giving the Sacred Scripture to the Bishop Joseph of Edessa who accompanied Thomas of Cana to Malabar (Punnose and Chacko, 1991); or Thomas of Cana receiving the famous Copper Grants from the king Cheraman Perumal in the presence of a witness (Cherucheril, 1982). The witness is even named as Vikraman Chingan of Kaduthuruthy in the Parish Directory (2017).

Panel-3 (South)-Wrestling Scene

This scene has two figures in a wrestling position forming a circle, supported by two strong figures with clubs in their hands in perfect action, and on the left side is a mythical lion (Vyali motif) mounted over a crab (Hosten, 1924; Kurisummoottil, 2008). Similarly, it could be two men rolling around by holding the legs of each other and being watched by three individuals (Jose, 2017). Interestingly, some believe that the carving represents the round dance forms (Parichamuttukali, Margamkali etc.) performed by the Knanite community.

Panel-4 (South-East)-Cavalry Scene

This panel of a cavalry scene, having on either side a man with shield and sword on horseback, each fighting the other, has been unanimously taken as a battle scene by researchers (Hosten, 1924; Kurisummoottil, 2008).

Panel-5 (East)-Infantry Scene

The infantry scene consists of two pairs of soldiers with swords and shields, each group fighting the other ferociously. Kurisummoottil (2008) traces two tiny images of beasts at the centre of the panel, perhaps signifying their respective kingdom emblems. He believes that the figure on the left side wears a European hat, and the right side confronting figure has an Arab-Turkish turban, while the soldiers at the extreme ends are from the local army. Hosten's (1924) interpretation is interesting as he believes the panel represents two men (and two dogs) on either side, each group of two fighting the other.

The panels 4 and 5 are battle motifs. It is, however, not clear if these scenes are representation of a major historical event. One possibility is that it refers to the battle at Kodungallur in 1524, fought between the King of Kodungallur supported by the Portuguese and the Zamorin of the Calicut assisted by the Muslims soldiers-a war that has traditionally played a key role in the establishment of the Knanite community of Kaduthuruthy. Another event which Kurisummootil (2018), suggests is a battle in 1550 at Vaduthala near Vaikom, between the King of Cochin and the Portuguese against the King of Vadakkankur, which ultimately resulted in the expulsion and exile of the Knanite community from Kaduthuruthy. A different speculation is that, the Syrian Christians were well known warriors and experts in martial art, and the carvings represent a scene from their social life (Cherucheril, 1982).

Panel-6 (North-East)-Crossed Fish and Elephant vs Bull

There are two scenes in this panel. The left scene has two crossed fishes and the right scene is a fight between an elephant and a bull. Hosten (1924) comments that both have a common head, the head looking like a bull's head from one side and like an elephant's head from the other side.

Panel-7 (North)-Elephant vs Lion

The panel is a depiction of a combat scene between a mythological monster (Vyali) and an elephant (Kurisummoottil, 2008); or a fight scene involving lion, elephant and panther (Hosten, 1924).

The panels 6 and 7 are fight motifs involving animals (fish, elephant, bull, lion etc.) and mythical creatures (Vyali). The fish symbolizes Christ himself and the sign was adopted by the early Christians before the cross became popular. Elephants are favourite subjects in Indian art forms, whereas mythical creatures suggest supernaturalism or divinity (Kurisummoottil, 2008)

Panel-8 (North-West)-Tiger Hunting Scene

This is the only panel with a hunting scene. The scene is displaying two men hunting a tiger with spears. Tiger-hunt is a favourite sport in India and thus became a theme for art work says Kurisummoottil (2008), and hunting was popular among the Syrian Christians argues Cherucheril (1982).

CORNER SECTION-ELEPHANTS

At the four corners of the pedestal are elegantly carved four stone elephants about a feet in height. They take vigilance of the four cardinal points and act as the guardians of the sacred space, resembling the dikpalakas (guardians of the quarters) motif of the traditional Indian art (Kurisummoottil, 2008). Even around a century ago, these statues were in a mutilated state as attested in the Travancore Archaeological Series (Volume 7, 1931). It is true that the elephant sculptures a worn-out appearance today, yet one can appreciate the skill of the artisan by observing the fine details and considering that they have remained intact for centuries amidst the harsh weather and unfavourable conditions. The elephants at the eastern side (North-East and South-East corners) have full chains encircling their bellies, whereas the ones at the western side (North-West and South-West corners) are half-chained.

The largest moulding of the pedestal is the bottom square layer which contains certain important elements to be noted. The layer can be again divided into upper, middle and bottom registers.

UPPER REGISTER

The upper register has a long row of animal and bird motifs in procession. There are a total of four such registers, one for each side of the square. The old song of ‘Kaduthuruthy Cross' (Lukas, 1910) lists 6 animals (lion, elephant, tiger, bear, stag and camel) and four birds (parrot, swan, peacock, and cock). Today, a significant share of these panels are not in good shape and it is difficult to decipher. Moreover, modern restoration efforts have resulted in irrecoverable damage to them, especially on the western side. At the time of Hosten's visit (1924), it seems these panels were in better condition, as he gives a detailed account of all the four sides. He observes 8 peacocks and a pea-hen (west); 5 peacocks, a dove and a tortoise (south); 6 peacocks, 2 cocks and unidentified bird or birds (east); and 2 lions, 2 oxen, 2 wild boars, a deer, a camel, a ram, a hare and an unidentified animal (north). We are therefore to understand that the peacock was the most represented motif and the animals were displayed only at the northern side of the upper register.

MIDDLE REGISTER

The narrow middle register has horseshoe shaped gable ornamentation with a winged face motif. There are four such motifs on each side of the square. Kurisummoottil (2008) compares the register to the convex cornice called Kapota in Indian architecture, and the gable ornamentations to Kudu or Nasika motifs, a feature originating from Buddhist Chaithya windows.

LOWER REGISTER

The lower register has the characteristic highly projected niches bordered by two pairs of trefoil crosses on each side.

THE FOUR NICHES

The niches are positioned at the four cardinal axis giving the square section a cruciform shape. Each of the four niches enshrines a rounded statue and they have a big roofed Nasika with an angel motif carved on top of it. On either sides of this big Nasika, in the right and left columns of the niche are two smaller nasikas with winged faces inside. Thus, on each side of the bottom square section of the pedestal there are 7 winged faces (4 on middle register and 3 on the niche).

Western Niche

There is no dispute regarding the identity of the statue enshrined in the western niche. This statue of Mother Mary holding infant Jesus is carved on the western axis of the cross and we saw the importance of this direction earlier. You can also observe that the face of Mary has been restored with cement and mortar.

Secret Chamber above the Western Niche

There is an interesting tradition about a secret chamber in the pedestal of the Kaduthuruthy Cross containing the relics of the Holy Cross of Jesus, brought to the site in the 15th century. Cherucheril (1982) claims that during his visit to Kaduthuruthy in 1922, Hosten lifted the upper stone of the secret chamber with an iron rod and showed a small case which held the relics to the public. In Hosten's account of 1924, he found a loculus closed with a stone and molten lead above the angel motif (Nasika) of the western niche, which was an indication of a relic being inserted. However, he says that the relics traditionally belonged to St. Stephen. Anyway, today we don’t have a clue of its whereabouts.

Northern Niche

The statue in the northern niche of a woman holding a grown up child is usually identified as St. Anne and child Mary (Cherucheril, 1982; Punnose and Chacko, 1991, Parish Directory, 2017). However, as the child here is in a blessing posture proper to Christ alone, Kurisummoottil (2008) assumes that the statue is of Madonna and infant Jesus. Hosten (1924) also identifies the statue with ‘Our Lady and Child’, but mistakenly places it inside the southern niche.

Eastern Niche

According to local narratives, the eastern niche enshrines the statue of St. Thomas, the Apostle (Cherucheril, 1982; Parish Directory, 2017). Nevertheless, Kurisummootil (2008) argues that the figure cannot be St. Thomas, as he is depicted with a Persian turban on head, and can only be a hierarch like Mar Joseph (Yausef) of Edessa (Uraha) who came with Thomas of Cana to Malabar. Strangely, Hosten (1924) identifies him as the 14th Century Catholic saint, St. Roch, holding a stick and showing his leg bare! There are others who consider the statue belonged to Thomas of Cana himself (Punnose and Chacko, 1991).

Southern Niche

The southern figure is generally believed to be that of Thomas of Cana (Cherucheril, 1982, Kurisummoottil, 2008, and Parish Directory, 2017). Hosten (1924) identifies the statue with St. Thomas, the Apostle, but has wrongly placed it under the northern niche. Alternatively, Punnose and Chacko (1991) has come up with the name of Kunnassery Manthri, who was a prominent 16th century Knanite leader and the minister of Vadakkenkur king according to Cherucheril (1982).

CONTINUOUS TREFOIL CROSSES

On either side of the niche are a pair of crosses separated by a vertical decorated band. Thus, from all four sides there are 16 crosses on the lower register of the cross. These equal armed crosses have continuous trefoil extremities, where each end bifurcate as large curls with a protruding bud in between. Scholars differ in their opinion regarding the type of the cross it represents from indigenous Kerala Sliba (Kurisummoottil, 2008); lotus cross (Hosten, 1924), Persian cross (Menacherry, 1973; Vazhuthanapally, 1990); St. Thomas cross (Cherucherl, 1982); and crosses with floral arms (James, 1979).

RAILING AND THE LAMPS

The pedestal is surrounded on all the sides by a railing with an entrance at the western end. On the top of the railing there are several oil lamps. According to my calculation there are 152 of them today, however, Wikipedia gives an estimate of 153, which is, of course, a more symbolic number associated with Christianity. In the 1924 report, Hosten describes of two sets of small metal vessels, each to hold oil and a wick for illuminations. Interestingly, even in the early 17th century, according to an original account from the year 1611, there were no fewer than 160 lamps at the pedestal of Kaduthuruthy cross, which burnt every night around it (cited by Reitz, 2011).

CONCLUSION

There is no doubt the largest existing open-air granite cross of Kerala is an impressive structure and has its origin from the late 16th century. However, if the structure today remains true to the original form or whether western elements were introduced afterwards is not easy to conclude. For instance, the crucifixion motif on the western axis of the cross would beg the question if the symbols of the Passion were used in Kerala before the Portuguese? James (1979) considers this a definite deviation from the traditional Thomas Christian practice and Hosten (1924) finds it puzzling and a deep mystery.

REFERENCES

Cherucheril, Mathew (1982)-Kaduthuruthy Valiapally-Knanayakarude Mathrudayvalayam (Malayalam)

Hosten, Henry (1924)-In Documentation: Kerala Churches-Church of Kaduthuruthy (Hosten Ms: 45-58), Tanima: A Review of St. Thomas Academy for Research (2010), Volume XVIII, No. 2

James, E. J. (1979, Thesis)-The Thomas Christian Architecture of Malabar- Ancient and Medieval Periods

Jose, Cyriac (2017, Thesis)-Cultural Landscape and Architecture of Medieval Churches in Kerala

Kurisummoottil, George (2008)-An Iconographic Explanation of the Open-air Granite Cross of Valiyapally, Kaduthuruthy, Harp, Volume 23

Lukas, P A. (1910)-Malayalathe Suriyani Christhianikalude Purathanapattukal (Malayalam)

Malekandathil, Pius (2003)-Jornada of Dom Alexis de Menezes

Menachery, James (1973)- Thomas Christian Architecture-In St. Thomas Christian Encyclopedia of India (George Menachery Edn.), Volume II

Parish Directory (2017, Mathew Manakkatt ed.)- St. Mary's Forane Church, Kaduthuruthy

Punnoose, C. K. and Chacko, A. T. (1991)-History of Southist Community, Chunkom Church, Kaduthuruthy Church, Cross, Other Summary (Malayalam)

Reitz, Falk (2001)-Is the Origin of the Granite Crosses in Kerala Foreign or Indigenous?

Vazhuthanapally, Joseph (1990)-Archaeology of Mar Sleeba

No comments:

Post a Comment